By Sienna Ballou

Part one: The Festival in Production

We’re just one day away from the first Open Rehearsal, meaning, the Festival season is upon us! I’m working on this post today from the staff lounge, where I can inconspicuously listen to Michael Sheppard rehearse on the piano. I’d be lying if I said my heart wasn’t fluttering in response to the experience of hearing music in the auditorium for the first time. Not only am I new to the Festival, but I’m also new to the Civic. So, it’s nothing short of exciting to hear Sheppard’s rolling notes fill the hall. It’s almost as if his sounds are giving shape to the space that just two days ago was filled with the noises of feet and metal, and the voices of stagehands—not that those sounds aren’t also exciting in their own way. In fact, when I entered the Civic for the first time three days ago, I experienced a kind of nostalgia as I was reminded of the dozens of other theaters in which I’ve spent hours and hours rehearsing during the weeks before performances. This nostalgia was provoked by a combination of small things: the kitchen with the half-filled pot of coffee that some early bird stagehand prepared, the smell of an auditorium in production, the empty dressing rooms that seem to bristle with the anticipation of occupation, and even the gestures of the stage and facility crew as they hung lights and sound equipment, built risers, climbed ladders, painted signs, and engaged in energetic conversations about their processes. All of this gave me the familiar feeling that this was a space in transition.

We’re just one day away from the first Open Rehearsal, meaning, the Festival season is upon us! I’m working on this post today from the staff lounge, where I can inconspicuously listen to Michael Sheppard rehearse on the piano. I’d be lying if I said my heart wasn’t fluttering in response to the experience of hearing music in the auditorium for the first time. Not only am I new to the Festival, but I’m also new to the Civic. So, it’s nothing short of exciting to hear Sheppard’s rolling notes fill the hall. It’s almost as if his sounds are giving shape to the space that just two days ago was filled with the noises of feet and metal, and the voices of stagehands—not that those sounds aren’t also exciting in their own way. In fact, when I entered the Civic for the first time three days ago, I experienced a kind of nostalgia as I was reminded of the dozens of other theaters in which I’ve spent hours and hours rehearsing during the weeks before performances. This nostalgia was provoked by a combination of small things: the kitchen with the half-filled pot of coffee that some early bird stagehand prepared, the smell of an auditorium in production, the empty dressing rooms that seem to bristle with the anticipation of occupation, and even the gestures of the stage and facility crew as they hung lights and sound equipment, built risers, climbed ladders, painted signs, and engaged in energetic conversations about their processes. All of this gave me the familiar feeling that this was a space in transition.

Over the last couple of days, I’ve seen the Civic Auditorium transform into the Cabrillo Festival home. And while the human effort that goes into this transition is clear, there’s still something pretty magical about it. Anyone who is familiar with the Civic knows that it is an incredibly adaptable space. Seven days ago, it was the venue for the Elton John tribute, The Rocket Man. Nine days prior it was the location for a five-day-long Aikido retreat. And before that, it held the Santa Cruz Derby Girls Double Header, a dance show, a gem sale, and countless other varied events. The history of the Civic is, of course, largely a musical one. It’s the regular venue for the Santa Cruz Symphony and, of course, it’s hosted the Cabrillo Festival for 27 years. When I walked into the Civic for the first time, I admit that I was surprised at how difficult it was to pin down what kind of space it was—its versatility was clear. The space seems to hold memories of past and future events and performances, and while I could feel that this was true, I still became curious about what some of those memories were. So, I decided to have some fun and find old Santa Cruz Sentinel articles that covered the happenings of the Civic. Countless events have passed in this space—far too many to cover here—but I thought that I would share a few of my finds.

Part Two: Civic Auditorium Flashbacks

This first image is a clip of a 1940 Santa Cruz Sentinel article describing the opening ceremony for the Civic. It begins, “Santa Cruz civic auditorium, aglow with life and light for the first time, opened its great capaciousness to 1500 townspeople last night. The Auditorium was open on the day of its dedication from noon to midnight. It took an estimated 5000 visitors out of the rain into the assembly hall and offices and rooms.” It appears to have been quite an engaging day, beginning with patriotic performances by local artists and groups, followed by a speech from the mayor, in which he dedicated the Civic to “the highest ideals of every man, woman, and child who enters this place through the portals of yon doorways,” and finishing with a professional talent show, which was 2/3 sold out before the initial dedication was over. You didn’t have to be there to feel the city’s pride for their brand-new auditorium.

This first image is a clip of a 1940 Santa Cruz Sentinel article describing the opening ceremony for the Civic. It begins, “Santa Cruz civic auditorium, aglow with life and light for the first time, opened its great capaciousness to 1500 townspeople last night. The Auditorium was open on the day of its dedication from noon to midnight. It took an estimated 5000 visitors out of the rain into the assembly hall and offices and rooms.” It appears to have been quite an engaging day, beginning with patriotic performances by local artists and groups, followed by a speech from the mayor, in which he dedicated the Civic to “the highest ideals of every man, woman, and child who enters this place through the portals of yon doorways,” and finishing with a professional talent show, which was 2/3 sold out before the initial dedication was over. You didn’t have to be there to feel the city’s pride for their brand-new auditorium.

(Santa Cruz Sentinel, Volume 103, Number 76, 29 March 1940)

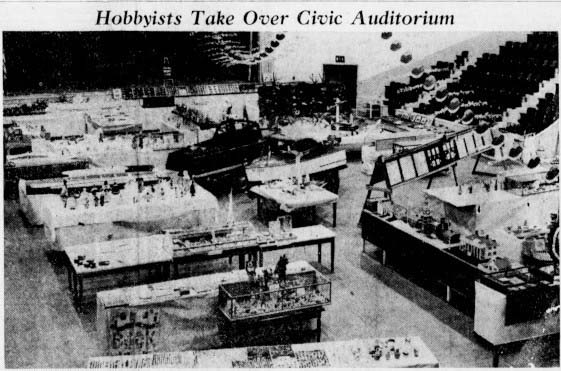

This next clip is from a November 1940 article which recounts the first annual Hobby Show hosted by the Junior Chamber of Commerce. The show included such displays as “John Strohbeen’s priceless display of mounted butterflies, Bill Sinkinson’s powerboat, Forrest Faneuf’s stamp collection, showing stamps issued commemorating the crowning of King George VI and queen Elizabeth; Bill Harry’s photographs of various types of locomotives, trolley cars and his miniature railroad, Mill L. Alice Halsey’s collection of antique button” and I couldn’t possible exclude “K. Smith’s collection of driftwood, which with little carving resembles sharks and snakes and prehistoric monsters.” I can’t help but wonder if my own collection of glass figurines would have been featured as well.

This next clip is from a November 1940 article which recounts the first annual Hobby Show hosted by the Junior Chamber of Commerce. The show included such displays as “John Strohbeen’s priceless display of mounted butterflies, Bill Sinkinson’s powerboat, Forrest Faneuf’s stamp collection, showing stamps issued commemorating the crowning of King George VI and queen Elizabeth; Bill Harry’s photographs of various types of locomotives, trolley cars and his miniature railroad, Mill L. Alice Halsey’s collection of antique button” and I couldn’t possible exclude “K. Smith’s collection of driftwood, which with little carving resembles sharks and snakes and prehistoric monsters.” I can’t help but wonder if my own collection of glass figurines would have been featured as well.

(Santa Cruz Sentinel, Volume 106, Number 120, 17 November 1940)

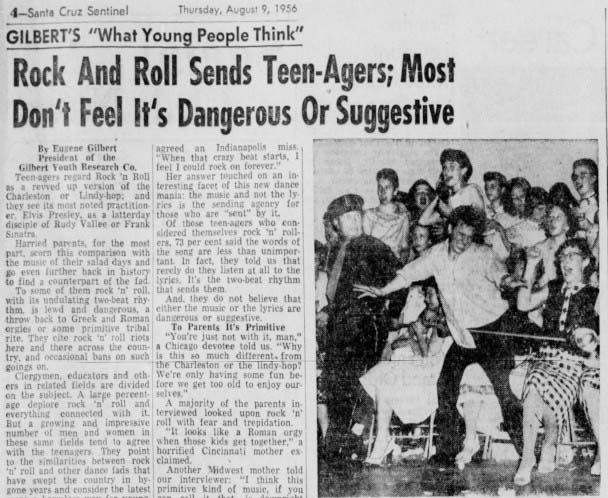

Many might have heard of the Santa Cruz Ban on Rock and Roll that occurred in 1956. The MAH has a great blog post by Marla Novo covering the ban. You can check it out here. Novo shares:

Many might have heard of the Santa Cruz Ban on Rock and Roll that occurred in 1956. The MAH has a great blog post by Marla Novo covering the ban. You can check it out here. Novo shares:

“Many Santa Cruzians packed the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium to see Saxophone sensation Chuck Higgins play his hit ‘Pachuko Hop.’ During the concert police entered the venue at 12:20 am and witnessed music that according to Richard Overton ‘excited the crowd to passion at times and it was feared that the crowd would become uncontrollable ‘(‘Authorities’ 1). Although it was only a few dancers at the venue, Overton and the police department took action under the belief that the dancing was “detrimental to both the health and morals of our youth and community” (“Authorities” 1).”

So, a ban was set in place, until City Manager, Robert Klein lifted it two days later. In response to the issue, several teenagers gave their opinions on the matter in an interview with journalist, Eugene Gilbert: “‘I don’t know exactly what the reason is, but it just sends me,’ said an Omaha enthusiast. ‘The rhythm carries me away,’ said an Indianapolis miss. ‘When that crazy beat starts, I feel I could rock on forever.’”

(Santa Cruz Sentinel, Volume 100, Number 188, 9 August 1956)

And here we have a 1979 segment on the Preservation Hall Jazz Band at the Civic. Tom Honig writes, “The Cavernous Civic Auditorium was about half-filled for the concert. But from the first chorus of the first song, the audience caught fire. Traditional jazz is jagged and imperfect music that comes together in an infectious way. And you’ll never hear it better than from this band.”

And here we have a 1979 segment on the Preservation Hall Jazz Band at the Civic. Tom Honig writes, “The Cavernous Civic Auditorium was about half-filled for the concert. But from the first chorus of the first song, the audience caught fire. Traditional jazz is jagged and imperfect music that comes together in an infectious way. And you’ll never hear it better than from this band.”

(Santa Cruz Sentinel, Volume 124, Number 155, 3 July 1979)

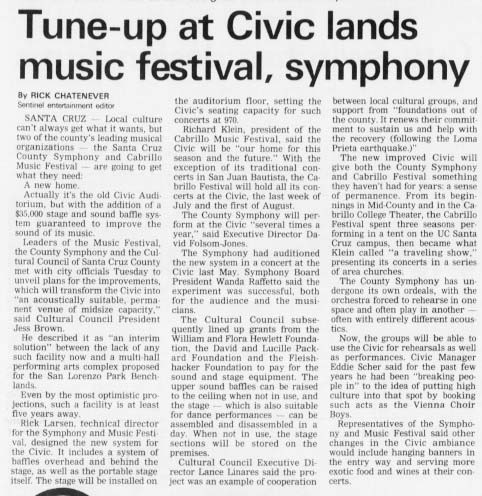

Jump forward to 1991, and the Civic was getting a tune-up before becoming the official home of the Cabrillo Music Festival! From 1963-1988 the Festival was held in a variety of locations, but after the occurrence of the Loma Prieta Earthquake, the city engaged in efforts to improve downtown facilities and it became important to incorporate the Festival in these efforts by centering it downtown and giving it a permanent space.

Jump forward to 1991, and the Civic was getting a tune-up before becoming the official home of the Cabrillo Music Festival! From 1963-1988 the Festival was held in a variety of locations, but after the occurrence of the Loma Prieta Earthquake, the city engaged in efforts to improve downtown facilities and it became important to incorporate the Festival in these efforts by centering it downtown and giving it a permanent space.

(Santa Cruz Sentinel, Volume 135, Number 84, 27 March 1991)

These are just a few of many sporting events, trade shows, festivals, and concerts that occurred at the Civic (I didn’t even mention the Beach Boys concert of 1964!) but you can check out https://www.friendsofthecivic.org/history for a great timeline.

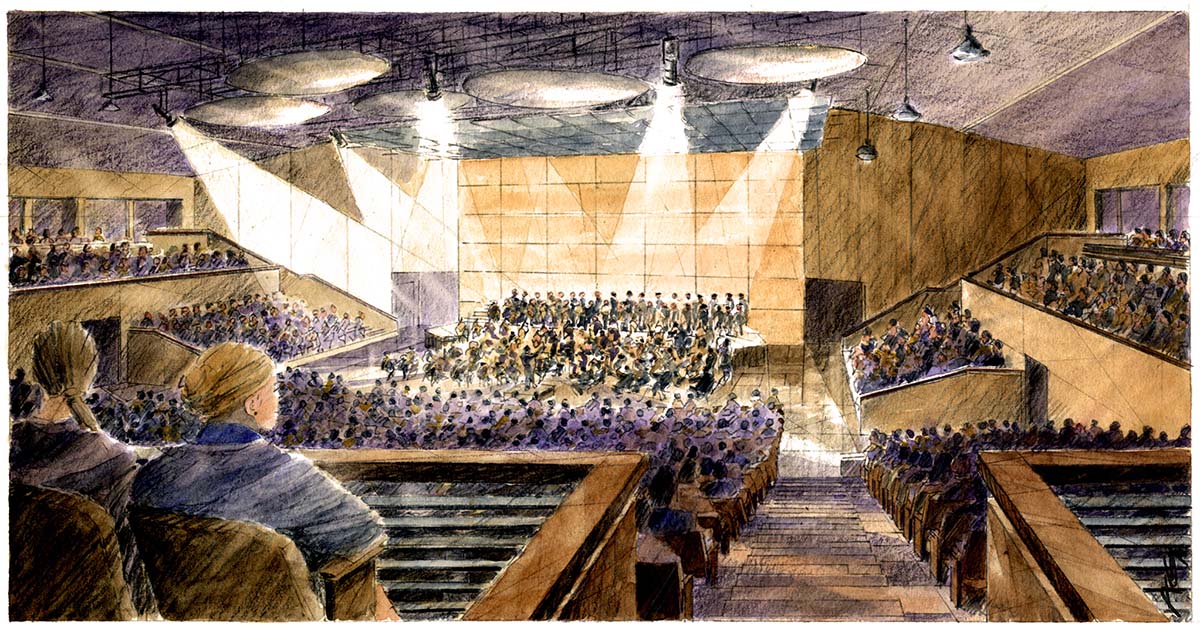

Now, in 2019, the Civic Auditorium continues to transform. The Friends of the Civic Auditorium are advocating for a renovation of the facility, so as to bring modern systems, new safety measures and a higher level of comfort to the historic building. It makes sense that as the performances that occur inside the Civic change with the times, so should the building itself.

This brief exploration of the Civic’s past just begins to skirt the surface of what a deep investigation of place would require. For example, I have yet to learn what was there before the Civic was built in the 1930s. It’s also important to recognize that the Civic, along with all of the buildings in Santa Cruz, sits on the traditional territory of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. “Historically comprised of more than 20 politically distinct peoples, the modern tribe represents the surviving descendant families of these historic groups” (https://amahmutsun.org/land-trust). All of these factors contribute to what I’m thinking of as the embodied history of the Civic–the history that is contained in its stone walls and in the ground beneath it. The history that leaves almost unnoticeable scuff marks or paint chips and that comes to the present again when someone is reminded of it by their own return to the building. For me, having an understanding of this history is important as I spend the next few weeks absorbing and reflecting on the music produced within the walls of the Hall. I’ve become interested in how my relationship with a place can affect my sense of my own body as a place for listening and experiencing music.

Space, Place, and the Listening Body

This process of learning about the place that is the Civic Auditorium has become important to me because I’ve been thinking about what it means to be an active audience member while at the Festival. By active, I mean that I’d like to consider the act of listening to music as a performance in itself. I recently encountered this idea in an article titled “Embodied sound: Aural Architectures and the Body,” by musicologist, Gascia Ouzounian. I’m interested in Gascia’s research on the experience of “situated, embodied listening.” This means listening that involves the entire body and is dependent on the space/place it occurs in. While Gascia’s article is centered around two sound installations each of which are intended to create sound experiences that can be felt in the body, I find her analysis to be useful for thinking of the body as a space in which to experience music while at the Festival. She frames the space of the body as influencing and being influenced by the space in which it engages in the act of listening. In my case, this space will be the Civic Auditorium. So, knowing a bit about what has occurred in the Auditorium in the past is important if I want to understand the present dynamics of the space. I’m hoping that this understanding might contribute to my own situated embodied listening experience.

Gascia describes her embodied listening process as an exploration of: “the intersection of sound, space and sensation as it occurs between [her] body, its surroundings and its imaginary points” (70). In Gascia’s descriptions of her listening experiences, she describes in detail her setting (where she is and who is around her), her internal and external sensations, the positions in which she holds her body, and the images and ideas that come to mind as she processes the recorded sound. She does not go into a traditional analysis of the sounds, but rather, as she describes, a “situated and embodied experience of sounds as they inform the realization of my body in relation to itself and to other bodies—social, physical and imaginary ones—that make up complex and unpredictable networks of space and place” (78). Reflecting on her listening of Maryanne Amacher’s Sound Characters (Making the Third Ear) (1999), which she played inside her car while parked at a San Diego beachside, she shares:

“By bringing Amacher’s music into this place, with its particular complex of social and physical dimensions and codes for relationships between bodies within these, I have disrupted it and produced an altogether new place. This is, in a practical sense, the power that exists in cultivating an awareness of one’s body in its relation to an environment.” (76)

What really excites me about Gascia’s reflection is the idea that a “new place” is conceived of through the interaction of sound, the listening/perceiving body, and the social and physical dynamics of the literal space in which the listening occurs. As someone who often experiences music through movement and dance, I’d like to see how I might go about listening to the concerts of the Cabrillo Festival with my whole body, rather than just my ears. Engaging in a situated embodied listening process means that I’m going to try and think about how the music might transform the space of my body into a temporary “place” within the place and space of the Civic. Here I’m thinking of the place as something specific and formed from experience, and space as something more abstract (the empty slate of the theater that I described earlier). Gascia provides a thorough distinction of space and place according to the theory of Henri Lefebvre, who in his book The Production of Space (1974) “helped launch a notion of spatiality that included in its scope the body, action and the constructed environment” (71). Thinking of my body as a space that is constructed by my listening experience will require me to remember that I am one of the thousands of people to have been in the Civic in its 75-years of existence, and of even more people who worked, and lived on the land prior to its construction. As I experience the resonance of sounds within the interior of the Art Deco building that has and continues to shape Santa Cruz’s history, I’ll think about how the music of the Festival shapes the place and space of the Civic, and how my own listening body fits into that shape.

Ouzounian Gascia.”Embodied Sound: Aural Architectures and the Body.” Contemporary Music Review, Vol. 25, No. 1/2, February/April 2006, pp. 69 – 79.